Creative Leadership Today

Creative leadership is an individual and collective practice of deliberately applying established or fostering novel creativity or innovation methods, frameworks, or approaches to challenging opportunities, problems, or other situations over time, while also questioning and refining the assumptions, definitions, and principles underlying these methods, frameworks, or approaches – including what creativity, innovation, and leadership mean for individuals, teams, organizations, markets, and business today.

This practice differs fundamentally from the creative leadership that predominated since at least the early 1970s. Whereas that earlier set of practices often relied on charismatic individuals and standardized (indeed, often proprietary and marketed) innovation frameworks within organizations, today’s approach recognizes a host of limitations exposed by cultural analysts’ critiques, creeping industry obsolescence, and what I’ve referred to elsewhere as the historical “rise and fall of creative leadership” (Slocum, 2025).

These limitations include creative leadership’s assimilation by entrepreneurs (and their funders), its institutionalization by the Leadership-Industrial Complex, its homogenization on popular digital and social media platforms, its reduction to a regimen of marketable, even commodifiable activities, and its growing disconnect from many of the realities of digital, data-driven, platform-based, and algorithmic capitalism. Creative leadership today emerges from this multifaceted reckoning, informed by both the aspirational potential and the documented shortcomings of its recent incarnations.

Learning as the Core and Driver of Creative Leadership

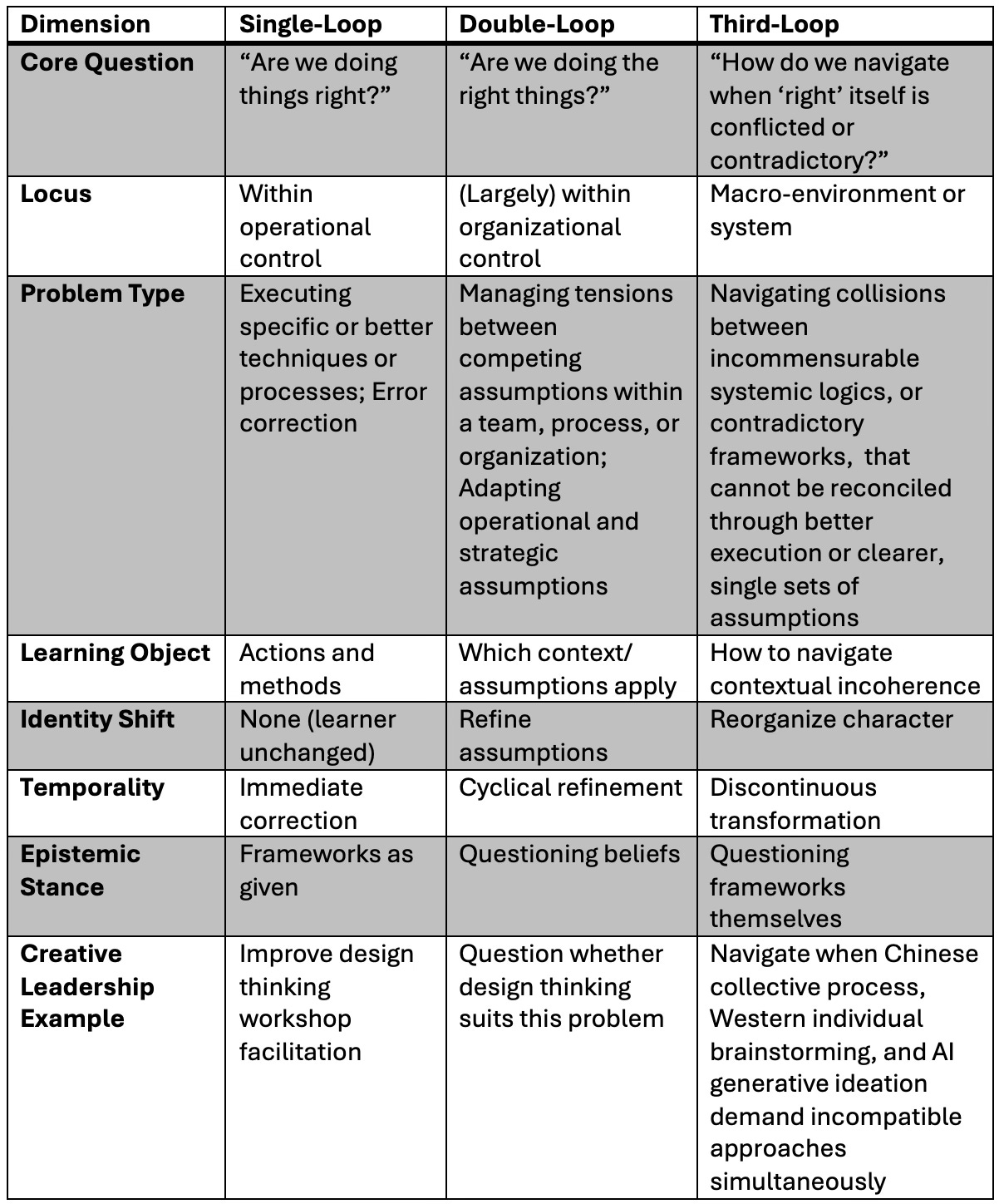

At its foundation, today’s creative leadership builds on organizational learning pioneers Chris Argyris and Donald Schön’s double-loop learning model, where leaders not only act with given tools or methods, however original or imaginative, to solve problems, seize opportunities, and drive innovations (identified in the single loop) but also interrogate and adapt the deeper assumptions, goals, and beliefs that shape those tools, outcomes, relationships, and actions (the focus of the second loop) (Argyris, 2005).

What distinguishes creative leadership now, however, is that it increasingly demands even more than this dual engagement. Creativity becomes essential not merely in executing actions or questioning assumptions but in navigating the increasingly complex learning required when the very frameworks through which we understand creativity, innovation, and leadership collide. Such multi-layered learning marks a crucial shift in how leadership must operate in today’s complex and fast-changing world, where creative capacity itself enables leaders to work across and through incompatible demands.

Consider ideas, models, tools, and methods like psychological safety, design thinking, cross-functional teams, digital whiteboarding platforms like Miro, agile methodologies, and dedicated innovation time. All were once breakthrough approaches that challenged conventional management wisdom. Today, these concepts and approaches populate business school curricula, guide corporate training programs, proliferate in online management posts, and help to shape the workflows of creative organizations worldwide. While many teams deploy them productively to foster genuine collaboration and breakthrough thinking, others apply them formulaically, transforming dynamic practices into rigid processes that can actually inhibit the very creativity they were designed to unleash.

The challenge for contemporary creative leaders therefore lies not in the implementation itself, however imaginative, of widely recognized and adopted creativity or innovation frameworks. Instead, the opportunity rests in continuously interrogating the local applicability and relevance of such frameworks, adapting them to specific contexts, and developing hybrid or alternative approaches that transcend their original limitations. In so doing, creative leadership treats even established creative methodologies as raw material for further innovation.

Contrary to the restrictiveness of previous commercial, policy-making, and academic formulations, and particularly around the work and leadership of cultural and creative industries, creative leadership today transcends traditional boundaries of title, discipline, or domain. It can be exercised by individuals, teams, or organizational collectives who envision new possibilities, reframe problems, make decisions, motivate others, and drive purposeful action. In doing so, creative leaders challenge the inherited boundaries between leadership, management, and entrepreneurship, blending the particulars of these pursuits into a flexible, practice-based approach to navigating uncertainty. Whether in operations, finance, culture, customer engagement, or strategy, creative leadership is now relevant across every function and every level of the value chain in every industry and marketplace.

This practice, however, is marked by a profound paradox: the creative leader must not only generate new opportunities, solutions, and innovations, but must also create new approaches to driving those innovations and solutions and formulate original understandings of creativity and leadership themselves. At a time when many creative tools and methods have become standardized, replicable, and even automated through digital and data-driven platformization and AI, what counts as creativity or innovation should itself being questioned.

Put differently, today’s effective creative leader can no longer rely solely on inherited frameworks or standards, again however ingeniously they may be deployed. Rather, leaders must develop context-specific methods of creative action and continually reassess and re-envision how creativity functions and even what it means in their team, organization, or ecosystem.

Leaders respond to this paradox in varied ways. Some become architects of their own creative theories, naming, refining, and evolving the mindsets, frameworks, and approaches they use. Others focus on the immediacy of leading, relying on intuition, improvisation, and instinct, leaving the articulation of their creative process to reflection, collaboration, or future analysis (or to others altogether). Both these approaches to reflexive understanding and positioning of leaders’ and their teams’ or organizations’ own activities and impacts can deliver value and both contribute to the living evolution of creative leadership knowledge and practice.

Yet the ways that storytelling and meaning-making capture and communicate this knowledge and practice vary for different leaders and in different situations. Their sundry approaches to recognizing and navigating the paradox point toward a fundamental reorientation in how we understand creative leadership itself.

The broader (re-)orientation outlined here demands flexibility not just in tactics but in worldview. Creative leadership today is protean and situational, not formulaic or universal. Just as contemporary artists question the role of art in society while producing individual works and responding to individual commissions, so too must creative leaders question prevailing models of organizational authority, value creation, and collaboration when responding to specific briefs and situations.

What worked yesterday might fail tomorrow, not because the method was wrong but because the terrain has shifted and people have evolved. As such, creative leaders must cultivate a repertoire of approaches and a judgment refined by experimentation, reflection, and sensitivity to context and other interpersonal, organizational, and business components. These conceptual dimensions become concrete in contemporary practice.

From Paradox to Triple-Loop Learning Practice

David Droga’s transformation of strategic marketing through Accenture Song demonstrates learning across both the first and second loops: deploying established creative methodologies while redefining what agency-client (and consulting) relationships can become in a data-driven economy. Satya Nadella’s cultural revolution at Microsoft shows how leaders learn double-loop capabilities through deliberate practice: he cultivated the capacity to question Microsoft’s identity by engaging diverse perspectives, experimenting with failure, and creating spaces for organizational unlearning before relearning could occur.

Virgil Abloh’s work across Off-White and Louis Vuitton challenged traditional boundaries between streetwear and luxury, while constantly interrogating the very concepts of authenticity and cultural appropriation in fashion. Similarly, creators in the creator economy like Emma Chamberlain or MrBeast don’t simply master existing platform algorithms (single loop learning) but actively reshape the definitions of entertainment, authenticity, and audience engagement (double loop learning), creating new frameworks that other creators then adapt and evolve.

The reinvention evident in these examples illuminates what some subsequent analysts identify as the foundation for “triple-loop learning,” which has remained an ambiguously formulated “deeper,” recursive, and metaphorical level of learning that potentially extends leadership beyond the dimensions of doing and thinking to that of the governing variables of situations and systems (Tosey, et al, 2011). This ongoing leadership work of reflecting on and reshaping systems alongside interpersonal and organizational interactions represents a natural extension of Argyris’s double-loop learning and remains essential to the creative leadership that I’m proposing here is built upon it.

Yet the effort to understand “deeper” learning should not devolve into a fixation on individual emotional or intuitive development that occurs at the expense of nuanced engagement with external contexts and the fostering of creative conditions. Nor can it swing simply toward an emphasis on future studies, strategic foresight, or technological transformations that diminishes the importance of individuals and human groups in favor of systemic change.

Instead, creative leadership today embraces what might be seen as a troika of micro-, macro-, and meta-level concerns, integrating personal development with organizational or other associational and interpersonal transformation and broader systemic awareness and change. This inclusive formulation points toward the need fo deeper learning, but existing conceptualizations of triple-loop learning remain insufficiently developed to address fully the systemic collisions and framework contradictions creative leaders actually face.

Such a more productive understanding of a third loop could address what prior approaches largely miss. Where previous theoretical formulations (like Tosey, et al.) focused on purpose and values, and where the double-loop framework, powerful as it remains, addresses assumptions largely within organizational or market bounds, a third learning loop should confront macro-environmental transformations that generate what anthropologist and social scientist Gregory Bateson termed “systematic contradictions in experience.” A productive third loop consequently should emerge not merely from further introspection about individual or organizational purpose or values but from learning prompted by often irresolvable individual or group conflicts between incompatible contextual demands.

Where double-loop learning questions assumptions within a coherent (technical, institutional, human relational, business, leadership) framework that can be clarified or corrected, third-loop learning develops a capacity for leaders to operate when systems collide and frameworks contradict one another and compete.

This distinction matters because global creative leaders increasingly face polycontextual environments where Chinese relational harmony, Western individual merit, European rulemaking, Gulf hierarchical deference, and AI-driven algorithmic logic make mutually exclusive demands simultaneously. The third loop addresses not only better problem-solving within given contexts but what Bateson called the “reorganization of character,” the transformation of the learner’s (and, here, the leader’s) own identity when navigating contextual incoherence that cannot be resolved through improved assumptions alone (Bateson, 2000).

In other words, where the second loop refines how creative leaders think and act, the third loop transforms who they become as they lead through paradigmatic instability. Creativity here becomes the capacity to generate novel responses to irreducible collisions and contradictions, including the transformation the leaders themselves, rather than the production of elegant solutions to soluble problems.

It is important to clarify that these three loops operate as interdependent dimensions of learning rather than hierarchical stages. Third-loop reflection on macro-environmental or systemic collisions both depends upon and potentially reshapes first-loop functional operations and second-loop assumptions. The relationship is genuinely cross-directional: systemic differences recognized in the third loop are both informed by functional specifics and business or operating model assumptions from the first and second loops and simultaneously shape how those operational and strategic dimensions develop differently across contexts.

Recognizing systemic differences in how Chinese versus Western contexts approach AI development, for instance, requires understanding specific technical and funding practices (first loop), business model assumptions about open-source versus proprietary approaches (second loop), and broader paradigmatic differences in how innovation and societal ecosystems function (third loop), with each dimension informing and being reshaped by the others.

The complexity inherent in navigating these differences exists across all three loops, though at different scales and with varying degrees of intensity. Where first-loop complexity may involve operational challenges in executing specific techniques or processes, second-loop complexity requires managing tensions between competing assumptions within an organization. Managing these tensions can itself involve navigating contradictory demands about how to structure operations, allocate resources, or define success across incompatible frameworks.

Third-loop complexity emerges from navigating collisions and contradictions between incommensurable systemic logics that cannot be reconciled through better execution or clearer, single sets of assumptions. Again, the three loops continuously inform each other: functional decisions shape which assumptions become salient, assumptions determine which systemic contradictions matter, and systemic contexts structure which functional operations prove viable.

Operating Across Colliding Systems and Contradictory Frameworks

Creative leaders can develop capacity across these loops through distinct but interconnected orientations and approaches. First-loop learning advances through iteration and experimentation with specific methods. Second-loop learning emerges from structured reflection, often catalyzed by performance failures that expose faulty assumptions. Third-loop learning develops through sustained exposure to incommensurable frameworks, typically requiring leaders to operate across cultural, technological, or organizational contexts where their existing paradigms visibly break down. Recognizing which loop should take priority requires attending to whether challenges stem from execution problems (first loop), misaligned assumptions (second loop), or framework incoherence itself (third loop).

Looking again at the example of artificial intelligence allows us to consider more precisely the reality of such contradictory business and operational frameworks while illustrating this interdependence across loops. Creative leaders cannot simply adopt AI tools (single loop) or question assumptions about creative processes related to those tools (double loop) because AI continuously destabilizes traditional frameworks through and around which creativity itself is understood and experienced.

For example, the tensions between ideation and execution, creator and audience, and novelty and value remain in perpetual flux as generative AI transforms each in incompatible ways. Boston College management and information systems professor Sam Ransbotham, in collaboration with the Boston Consulting Group, revealed that organizations achieving superior AI results prioritize “mutual learning between human and machine” that reshapes both parties, not sequential adaptation (2020).

DeepSeek’s development of competitive AI models on minimal budgets through open-source approaches exemplifies this interdependence across all three loops. Chinese ecosystem assumptions about collaborative versus proprietary development (third loop) both emerge from and reshape technical architecture decisions and resource allocation strategies (second loop), which in turn enable and are enabled by radically different operational practices around model training and deployment (first loop). The small-budget, open-source approach illustrates how differences in functional operations, technical and business model assumptions, and systemic understandings of building new technologies remain inseparable: each loop informs the others in ways that create distinctly different innovation pathways.

Western AI leaders confronting DeepSeek’s approach thus face not only technical competition (first loop) or strategic challenges about open versus closed models (second loop) but fundamental questions about whether their entire innovation paradigm remains viable and competitive, a potential third-loop collision demanding identity transformation rather than strategic adjustment.

In this case, creative leaders face the bind of needing to master AI’s current capabilities even as those shifting capabilities redefine what mastery means. That bind, in turn, requires the development of specific competencies: the ability to work with AI as thinking partner while maintaining critical distance from its outputs, the capacity to recognize when AI-generated solutions reproduce rather than transcend existing patterns, and skill in articulating value propositions for human creativity that don’t rely on scarcity or superior execution.

Dutch digital transformation researcher Rogier van de Wetering and colleagues has explored this requirement for “adaptive transformation capability” amid discontinuous change (2022). But the more profound leadership challenge involves developing what Bateson termed “meta-contextual perspective,” the ability to see through contexts rather than merely choosing between them, to lead when the ground itself remains unstable.

Cultural variations can present these contradictions with particular force. Chinese creative leadership operates, speaking generally, through a system of relational care, coordination, and collective harmony; Western creative leadership, by contrast, tends to prize individual attribution and merit-based advancement; European creative leadership works within carefully orchestrated and regulated shared standards for producing and evaluating work; Gulf creative leadership broadly emphasizes hierarchical respect and personal relationship networks.

Recent research by Cambridge Judge Business School’s Daniel Petersen and Keith Goodall (2025) reveals that Chinese managers experience Western multinationals, particularly those headquartered in the U.S., as strong on human capital development but weak on social capital cultivation, reflecting incommensurable cultural logics about how leadership care functions. A decade ago, cross-cultural management consultant Michael Gates similarly observed that, Gulf leadership models practice being “hard on issues, soft on people” within high power-distance structures, emphasizing eloquence and personal force in ways that differ markedly from both Western egalitarianism and East Asian reactive harmony (Gates, 2015).

These are not stylistic differences that code-switching resolves. They represent epistemological contradictions about what creativity means (individual breakthrough versus collective refinement), how innovation emerges (disruption versus incremental improvement versus consensus-building), and what constitutes legitimate “creative authority.” The differences call upon leaders, whether through experimentation, collaboration, reflective practice, or self-transformation, to come to terms with and find paths among conflicting mindsets and meanings, contexts, cultures, and worldviews.

Third-loop learning requires creative leaders, for instance, to navigate situations where Chinese partners expect relationship-first decisions while Western boards demand data-driven rationales and European regulators expect compliance while Gulf collaborators require hierarchical deference – and all this simultaneously, not sequentially. Such coordinated understanding and engagement demand precisely this identity transformation: not becoming culturally fluent but developing capacity to hold contradictory cultural frameworks without synthesizing them into false coherence.

The creative leader must learn to operate in the contradictions and collisions themselves, building what might be understood as polycontextual capability where one’s own assumptions about creative leadership become visible as assumptions rather than universal truths, enabling genuine navigation of systematic differences in how cultures structure creative possibility and realization. Leaders develop this capability not through cultural training programs but through extended practice leading across contexts where their default frameworks fail, learning to recognize the discomfort and dissonance of paradigm or systemic collision as signal rather than noise, and cultivating what might be termed “reflexive disorientation” as a productive leadership state.

Reflexive, Relational, and Historically Grounded Creative Leadership

Learning to navigate these contradictions is rarely a solitary pursuit. Leaders develop third-loop capabilities through sustained dialogue with peers facing similar paradigmatic tensions, through collaborative reflection on shared failures, and through building communities of knowledge and practice that make contradictions discussable and actionable rather than sources of shame and withdrawal. This collective dimension proves essential because individual leaders cannot typically generate sufficient perspective on their own paradigmatic limitations.

Together, these collisions and contradictions are vividly illustrated in contemporary creative leadership. TikTok’s Shou Zi Chew navigates irreducible tensions between US national security frameworks demanding data sovereignty, Chinese governmental expectations around content and control, and global user demands for algorithmic personalization. His efforts are noteworthy because these demands cannot be sequentially addressed or synthesized into a single coherent policy. ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming’s relocation to Singapore while maintaining Chinese citizenship embodies, at a geopolitical level, the identity transformation Bateson described: not resolving the US-China contradiction but learning to operate within it (Fortune Asia, 2024).

Similarly, leaders at global marketing and communications holding companies like WPP and Publicis navigate contradictions where clients simultaneously demand AI-driven efficiency, human creative authenticity, and protection from AI-generated mediocrity and slop.

Such complexity and contradictions cannot be “aligned” or “balanced” through better strategy (often a priority of double-loop learning); rather, they require the emergence of a capacity to lead when “efficiency,” “authenticity,” and “protection” mean incompatible things to different stakeholders. Reed Hastings’s Netflix transformation has involved continuous operational and business model shifts – from DVD rental to streaming platform to content producer to global entertainment network – each requiring not just strategic pivots but fundamental reconceptions of what Netflix was becoming, often while maintaining multiple leadership identities simultaneously for different markets and regulatory environments.

Whereas Nadella’s Microsoft transformation exemplified double-loop learning through questioning organizational identity within a coherent technology paradigm, Hastings navigated systematic collisions between building a technology company and leading a content studio, a disruptor and an establishment player, a Silicon Valley innovator and a Hollywood producer. These identities, in brief, demanded the simultaneous embrace of what had traditionally been incompatible strategic logics.

Three Interdependent Learning Loops for Creative Leadership

To reiterate, the three loops of learning – operational improvement, assumption questioning, and framework contradiction and systemic collision navigation – operate as interdependent dimensions rather than sequential stages, each informing and being shaped by the others within historical contexts.

In this regard, it is also imperative to understand creative leadership today as inherently historical. Claims that creativity is a timeless human capacity, often vaguely conceived in terms of artistry or imagination, ignore its profound contextual variation over time. Particularly in combination, leadership and creativity have been understood differently in medieval guilds, Renaissance workshops, artisanal associations, factory systems, industrial corporations, and digital networks. Today, we lead creatively within ecosystems increasingly shaped by entrepreneurial agility, data flows, distributed agency, platform economies, and machine learning.

The implication is clear: creative leadership is not just about future-thinking but about understanding that our own present positions and conditions are constructed through historical awareness, self and cultural literacy, and specific social, economic, and technological contexts, meaning that the tools and assumptions we inherit need to be regularly re-evaluated for their relevance. Historical consciousness itself becomes part of a learning practice when leaders deliberately study how past frameworks emerged, succeeded, and failed in their contexts, using this understanding to recognize when their own frameworks have become artifacts of conditions that no longer obtain.

To lead creatively today therefore means to embrace multiple responsibilities: to act decisively and to reflect systemically, to navigate contradictions and collisions without false resolution, and to recognize how operational decisions, strategic assumptions, and systemic contradictions continuously shape each other. It means both doing and questioning, executing and reimagining, managing the short-term while shaping the long-term. All that needs to be done while also developing the creative capacity to hold incompatible demands in productive tension while understanding how specific practices inform broader paradigms and vice versa.

Put differently, and in the words of a pair of contemporary Italian economists, this leadership is based in “a learning process that necessarily involves behavioral changes as the result of cognitive changes (modification of deeply held values, beliefs, and assumptions)” (Auqui-Caceres & Furlan, 2023: 757). Such a process takes on special import when leading other creative people, who each bring their own evolving experiences, priorities, and perspectives, and when enabling creative collectives and communities.

Here, creative leadership becomes not merely personal but relational, involving the delicate and, unavoidably now, technologically mediated balance of individual autonomy with collective goals through dialogue, empathy, negotiation, and shared inquiry. As a practice, creative leadership thus turns fundamentally on an openness to and embrace of learning in the toggling between creative actions and reflections, between single-loop efficiency and double-loop effectiveness and triple-loop transformation, recognizing that these modes of learning remain interdependent rather than isolated.

In our uncertain times, we cannot lead by using received ideas as autopilots – or reactive copilots, like prompt-dependent AI models, or even agentic partners – however creative they may initially appear or once have been. We need instead to lead with adaptive purpose and self- and contextual intelligence, questioning what we’re doing, why, where, and with whom, continually remaking both the tools and the terms of our leadership.

Creative leadership is not a fixed model, school, or identity but an individual and collective practice: deliberate, evolving, and generative. It develops through years of reflective experience and active learning, often accelerating when leaders encounter contexts that fundamentally challenge their existing repertoires and mindsets. It is guided by the awareness that leading creatively today is not only about driving innovation but also about shaping and re-shaping meaning, growing ourselves and others, challenging institutions and systems, and stewarding possibility through all levels of learning.

The imperative today ranges from improving what we do, to questioning what we assume, to transforming who we become amid paradigmatic instability, always recognizing that these dimensions inform and depend upon each other in the ongoing learning and practice of creative leadership.

References

Chris Argyris (2005) “Double-loop Learning In Organizations: A Theory of Action Perspective,” in Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development, eds. Ken G. Smith & Michael A. Hitt, New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 261-279; https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199276813.003.0013

Mercedes-Victoria Auqui-Caceres and Andrea Furlan (2023) “Revitalizing Double-loop Learning in Organizational Contexts: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda” (Review Article), European Management Review 2023, 20: 741–761; https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12615

Gregory Bateson (2000) Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000; 1972.

Fortune Asia (2024, May 8) “TikTok’s Lawsuit Against the U.S. Reveals Billionaire ByteDance Founder Zhang Yiming is Living in Singapore While Keeping His Chinese Citizenship,” Fortune Asia, May 8, 2024; https://fortune.com/asia/2024/05/08/tiktoks-lawsuit-us-billionaire-bytedance-founder-zhang-yiming-living-singapore-china-citizenship/

Michael Gates (2015, May 27) “Cross-Cultural Factors in Leadership in the Middle East,” Cross-Culture Blog; https://www.crossculture.com/cross-cultural-factors-in-leadership-in-the-middle-east/

Daniel A. Petersen and Keith Goodall (2025) “Leadership Development in the Cross

Cultural Context of China: Who Really Cares?” International Business Review 34(3), April, 2025; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2025.102400

Sam Ransbotham, Shervin Khodabandeh, David Kiron, François Candelon, Michael Chu, and Burt LaFountain (2020) “Expanding AI’s Impact With Organizational Learning,” MIT Sloan Management Review and Boston Consulting Group, October 2020; https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/expanding-ais-impact-with-organizational-learning/

David Slocum (2025) “The Rise and Fall of Creative Leadership,” Crafting Leadership Substack, February 20, 2025; https://creativeleadershiphub.substack.com/p/the-rise-and-fall-of-creative-leadership

Paul Tosey, Max Visser, and Mark NK Saunders (2011) “The Origins and Conceptualizations of ‘Triple-Loop’ Learning: A Critical Review,” Management Learning 43(3): 291-307; https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1350507611426239

Rogier van de Wetering, Patrick Mikalef, and Denis Dennehy (2022) “Artificial Intelligence Ambidexterity, Adaptive Transformation Capability, and Their Impact on Performance Under Tumultuous Times,” In Savvas Papagiannidis, et al., eds., The Role of Digital Technologies in Shaping the Post-Pandemic World, I3E 2022, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13454, Cham: Springer International Publishing; https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-15342-6_3